Nov

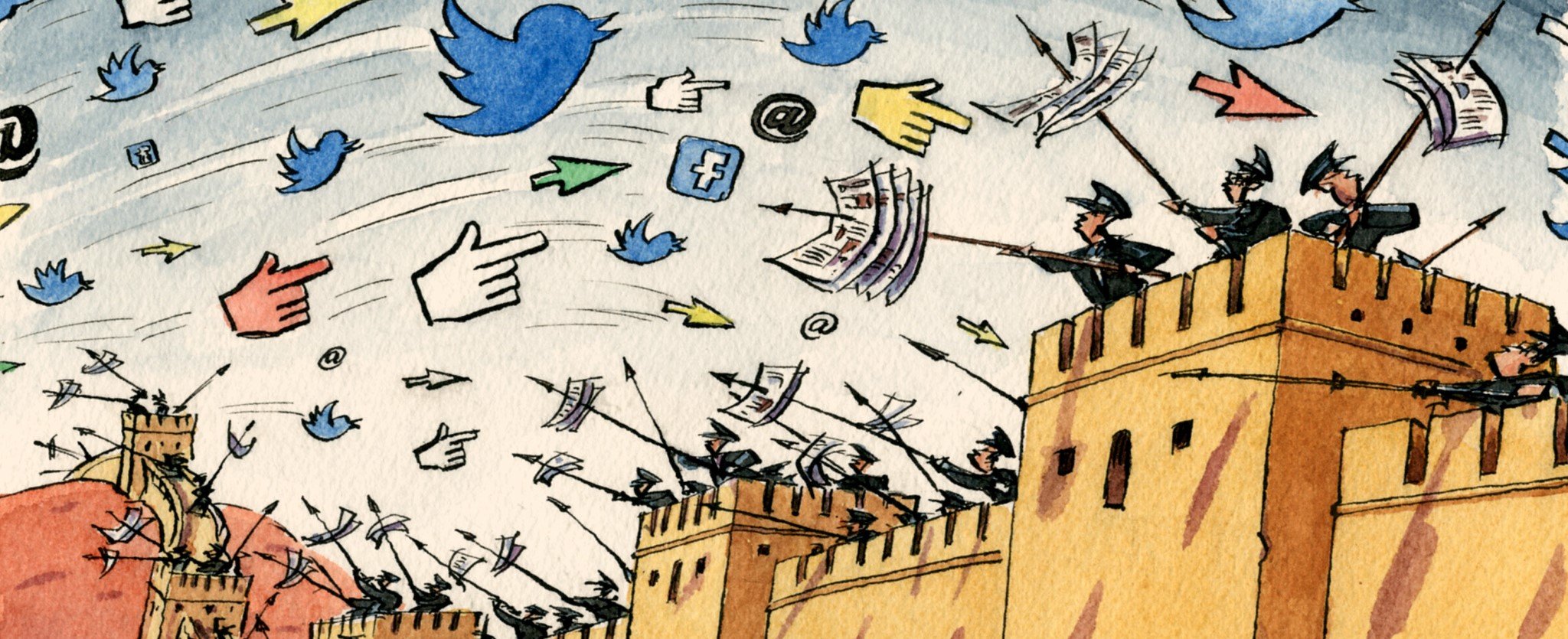

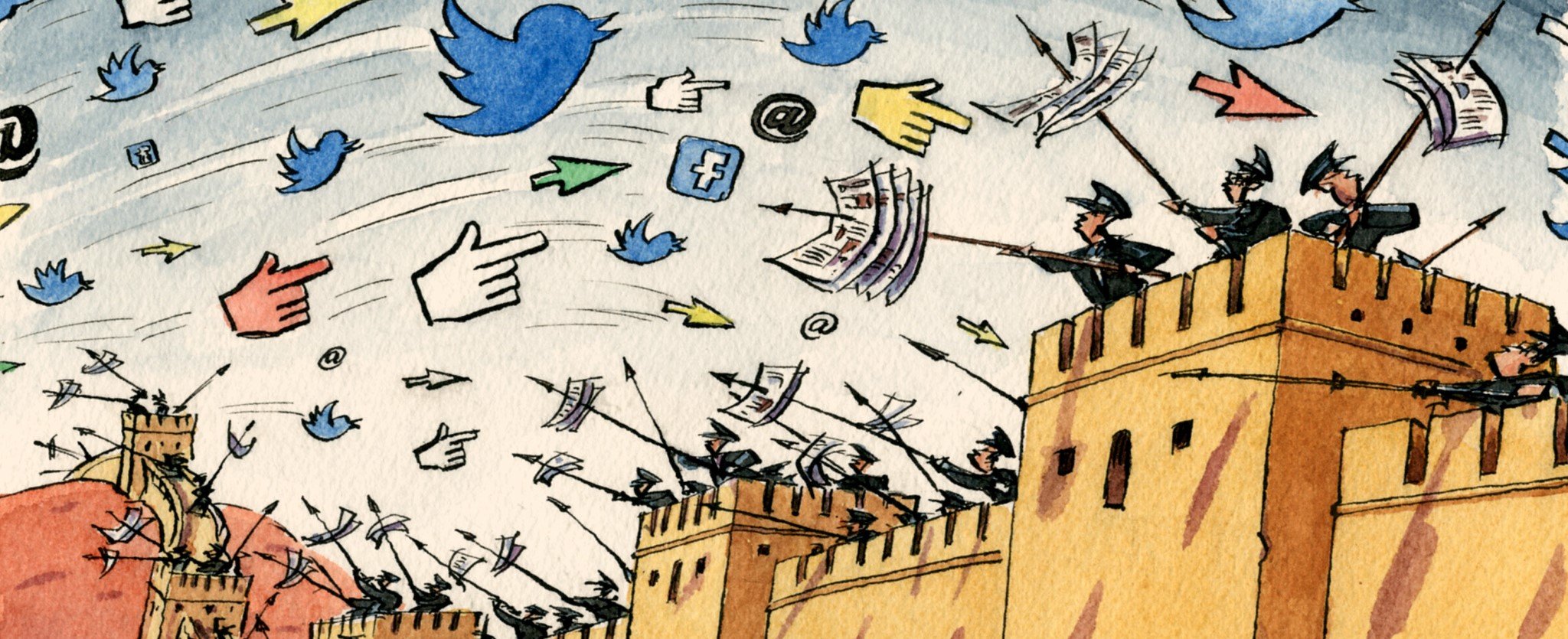

Pretty much all analysts acknowledge that censorship-related practices tend to be ubiquitous in China, with the main debates revolving around their effectiveness (or lack thereof). Of course, there is the occasional contrarian analyst who believes the issue is blown out of proportion but for the most part, the “Is censorship a significant issue in China?” question is hardly one we can consider controversial.

International organizations inevitably end up hitting the final nail in the coffin of this topic:

- The Freedom House NGO puts forth one of the most direct perspectives, with the Chinese press achieving its worst possible rank of “not free” in light of the fact that an entire system of incentives (with journalists and institutions who comply being financially as well as otherwise rewarded) and deterrents (with those who refuse to embrace the censorship paradigm being carefully monitored and drastically punished) has been built around censorship of the press

- On a similar note, Reporters Without Borders also gave China their worst possible ranking, with “very serious” being the lowest a nation can rank on their 5-point scale

- The OpenNet Initiative made it clear that whether we are referring to political channels or social media/Internet-related ones, censorship is unfortunately both running rampant and proving to be effective

… the list could on and on.

In a nutshell, journalists in particular or opinion formers in general have very little in the way of incentives to report on the various problems China is dealing with in an open and revealing manner. Such individuals usually find themselves censored and professionally ostracized at best and at worst… let’s just say movie scenarios are not far-fetched when compared to the realities in China.

On the other hand, opinion formers who embrace this reality frequently end up being on the receiving end of many career-related perks. Sometimes these perks involve direct monetary and position-related gain, for example receiving promotions if they work for various state-run or state-controlled entities as well as indirect ones, perks which revolve around influence and being more or less able to also leverage it without worrying about consequences.

What does the general public have to say about this?

Time and time again, psychologists have made it clear that due to phenomenon types such as self-censorship, it is difficult to put one’s finger on the pulse of society with respect to this sensitive topic. It’s perhaps even more so a matter of common sense, logic and game theory than it is something that pertains to psychology. After all, an effective censorship enforcement apparatus makes the average citizen believe that he or she is constantly monitored and as such, most people act the part. This means that, should they be asked to voice their opinions about matters such as censorship, they are quite likely to hide the truth due to being afraid of potential consequences.

Therefore, the answer to the previously posed question is simply that we don’t know. However, it is worth pointing out that an educated population is far more difficult to keep in check through such methods than an uneducated one. As such, as the prosperity of China continues its upward trajectory, the education level of the average Chinese citizen cannot help but also be affected in a positive manner. It would be quite short-sighted to assume that an increasingly educated population will continue blissfully tolerating the censorship status quo in China but at the same time, it is next to impossible to predict when a trend reversal will take place.

What about large Chinese companies, how are they positioning themselves?

Once again, it becomes a matter of simple economics in general or game theory in particular to understand that many Chinese companies such as Tencent or Baidu are on the receiving end of this equation. Why? Simply because pretty much all foreign competitors are negatively affected by the censorship situation in China and as a result, gaining as well as holding on to market share becomes far easier.

From “new world” search engines such as Baidu and social media platforms or instant messaging services to “old world” TV or radio stations, the Communist Party of China has made it a goal to control or at the very least try to control the narrative and public perception equation in China. Needless to say, there are inevitably winners in this scenario as well, with companies which display a pronounced willingness to comply being generously rewarded, either directly (through financing, for example) or indirectly (as a result of potential competitors being eliminated from the equation).

Can this status quo persist indefinitely?

Most definitely not.

Whether we are referring to technical difficulties associated with enforcing censorship such as the possibility of bypassing the Great Firewall of China (a topic we have dedicated an entire article to) or the previously-mentioned trend when it comes to education, let’s just say enforcing censorship was far easier during the days of the (in)famous Cultural Revolution of 1966 than the present. It remains to be seen how or even if the tide will turn and we will put an end to this post by simply making it clear that for reasons outlined in this article as well as many others, imagining scenarios in which it DOESN’T happen tends to be next to impossible.