Aug

When you have two historical figures such as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping who cast remarkably wide shadows, one problem which arises is that historical accuracy tends to sometimes also be buried under those shadows. In an earlier article, we’ve made it clear that not enough attention is usually given to Zhou Enlai despite him being a key piece of the Chinese history puzzle.

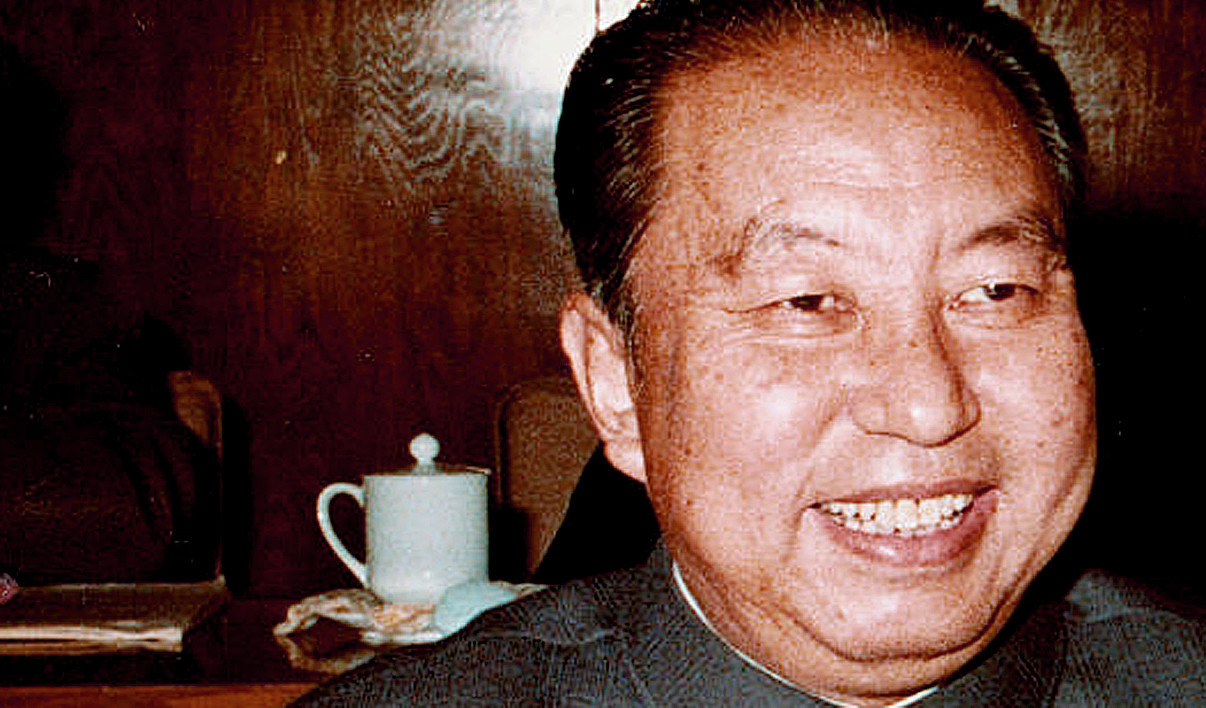

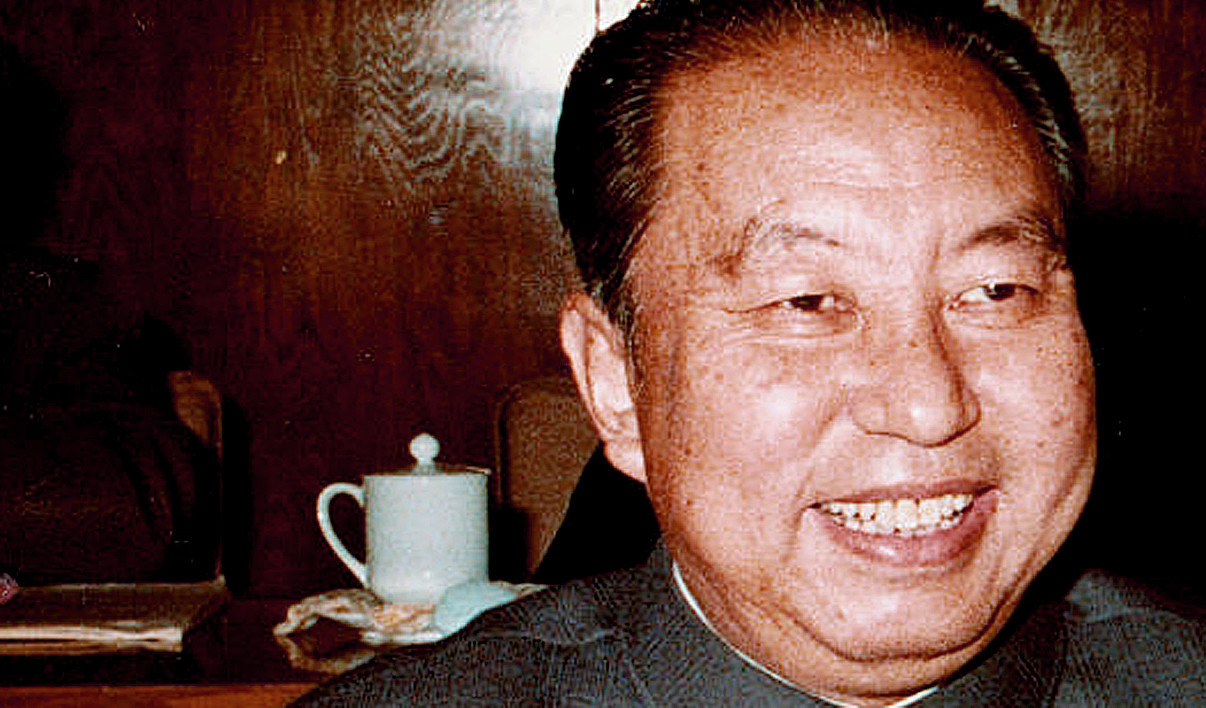

Today, it’s time for the person who became the acting premier after Zhou Enlai’s death to be in the proverbial spotlight: Hua Guofeng. Furthermore, Hua Guofeng was ultimately chosen by Mao Zedong to act as the permanent premier of China and even became the chair of the Communist Party of China after his death.

As such, can Hua Guofeng be considered Mao’s successor?

Technically speaking, yes… but in practical terms, no. As tempted as one may be to draw a parallel between Hua Guofeng and Zhou Enlai in a way which considers them both highly influential historical figures who just so happened to receive less attention due to being overshadowed by “larger than life” characters such as Deng and Mao, it would only be a partially accurate parallel.

This is primarily because, no, Hua Guofeng was not as much of a key figure as Zhou Enlai. Instead, it would perhaps be more realistic to consider him a transitional figure. Not as influential as someone such as Zhou Enlai but, nonetheless, a person that needs to be included in China’s historical puzzle so as to paint an accurate picture of reality.

Simply put, Mao found himself in a bit of a predicament toward the end of his life. As mentioned frequently here on ChinaFund.com, Mao Zedong was a die-hard ideologue, in contrast to the far more pragmatic Deng Xiaoping and even Zhou Enlai. However, toward the end of his life, geopolitical circumstances forced him to become more pragmatic and open to solutions which would have been considered unacceptable during let’s say the days of the Cultural Revolution, for example establishing a closer relationship with the United States.

This left him with a difficult choice with respect for China’s future: should the nation continue to be led in an ideologically rigid manner or is it time to become more flexible? This dilemma is illustrated by the two factions that fought for influence toward the end of his life: on the one hand, the extremely ideology-driven Gang of Four (Yao Wenyuan, Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao and even Mao’s third wife, Jiang Quing) and on the other hand, the more pragmatic/moderate Deng Xiaoping group.

Hua Guofeng ended up representing a compromise solution.

On the one hand, he was not a so-called radical Maoist but on the other hand, he wasn’t perceived as having overly close ties to the Deng Xiaoping faction either.

However, surprisingly or even as a shock to many, his actions shortly after Mao’s death would end up proving to be a game-changer for China. Just four days after Mao Zedong died, Hua had the (in)famous Gang of Four arrested and paved the way for the rehabilitation of Deng Xiaoping, culminating with Deng once again receiving his position of vice premier.

Things however wouldn’t end there, with Hua Guofeng essentially handing over his power to the Deng Xiaoping faction one step at a time, from letting Deng supporter Zhao Ziyang take his role as premier in 1980 and being replaced by Hu Yaobang (another supporter of Deng Xiaoping) as the chairman of the Communist Party of China in 1981. While he remained a Central Committee member for almost two more decades… needless to say, he essentially “gifted” his political power to the Deng Xiaoping faction.

His legacy?

Let’s just say this is where things get tricky. On the one hand, many are quick to dismiss Hua as a rather unimpressive political/historical figure and leave it at that. However, the fact that his actions after Mao’s death greatly influenced China’s future cannot be denied. What if decisive action had been taken against Deng Xiaoping’s faction rather than the Gang of Four? What if Hua had decided to aggressively hold on to his political power? Needless to say, it isn’t difficult to think of quite a few scenarios in which decisions of Hua Guofeng would have led to potentially disastrously destabilizing outcomes. Yet that didn’t happen and as a conclusion, even if only for this fact alone, it might be wise to include Hua as a small piece of the Chinese puzzle we are building, a piece which helps us understand the subtleties of China’s political life without which our perception of reality would be incomplete at best.